Epiphany is the summary of the Christmas season. Meaning “revelation” or “disclosure”, this day represents salvation being extended beyond the Jews to the whole world, as typified in the story of the Magi. In many traditions, it is celebrated as something of a Second Christmas that keeps us in awe of the Infant God in a manger.

Read Matthew 2:1-12

In an era of Herodian power-grabbing and Religious lethargy, we have an opportunity to reclaim the joy and awe of those who move towards Jesus in humble worship.

It is important to recognize that faithful biblical interpretation involves our entering into the world of scripture, considering the intent of the author and the perspective of their first audience, then the posture of the characters in the story. We can ascertain by the way in which Matthew’s gospel was written that his primary account of Jesus’ life is for his fellow Jews, beginning with a genealogy that, as we discovered several weeks ago, would contain several memory markers for his hearers that reminded them of the way God was moving through a particular bloodline within their people to bring about the Messiah. Even there, right at the beginning, Matthew is subversively challenging their assumptions about purity and worthiness by mentioning Gentiles who were woven into the story of Israel and the vital role they had to play.

We can then see once more in this passage that Matthew is subverting the standard wisdom of their day in terms of who is favored and worthy to receive the gift of the Messiah, and by extension, our own assumptions about how power and privilege work in this new world. At the advent of the Jesus story we are invited to consider which spirit we embody when seeking out the Infant God.

Let us consider the primary players in this tale: Herod, the teachers of the law, and the Magi.

The Herodian spirit utilizes religious language and imagery as a way to prop up fraudulent power, which leads to conspiracy, corruption, and terror. We know a fair amount about the first King Herod (72-4 BC). He was a brilliant military mind, a general of Jewish and Arab ancestry in the Roman army who was rewarded with the throne over Judea for his loyalty to Caesar. One of Herod’s major projects during his reign was to reconstruct the second temple in Jerusalem, thus confirming the support of the religious elite class for his spurious claim to power. His tenure was pockmarked with suspicion and paranoia, as he had two sons strangled for conspiracy, his wife surveilled and eventually killed out of jealousy, and over 300 public servants assassinated for suspicion of rebellion. When he died in 4 BC, Herod’s kingdom was broken into four pieces and bequeathed to his remaining sons, one of which is the Herod we encounter at the end of Jesus’ life.

It is no surprise then to discover that the revelation of the birth of the promised Messiah causes Herod “and all Jerusalem with him” great consternation, which leads to a mass killing of all boys in the kingdom under the age of two, mirroring Pharaoh’s terrible infanticide in the time of Moses. Perhaps it should not surprise us that the Magi, these visitors from the East, would first approach the palace of the Jewish king in search of a royal birth, as it is quite natural for one to assume salvation comes through the halls of power. Yet even they came to realize this fraudulent throne was a place of conspiracy, corruption, and terror; so they set out to Bethlehem in the suburbs to encounter God’s alternative inauguration.

Where do we see this Herodian spirit in our own time? Do we not also look to the seats of conventional power in our society for the salvation of the world - the White House, Buckingham Palace, and so on? I cannot help but contemplate the ironic historical juxtaposition between the Epiphany story and the insurrection at the Capitol Building on January 6th, 2021. That day contained at its core a cultural awakening to the realities of Christian Nationalism and conspiracy-laden extremism - crowds peppered with Christian symbols of crosses and flags, talk of messianic figures retaining power-through-force and retribution against all those standing in the way. The parallels are ghastly; and yet we would be remiss to assume that the Herodian spirit pervades only the political and ideological Right in our country. The postmodern world has become obsessed with analyzing power dynamics, often assuming that those in the majority have power and are corrupt, while those in any given minority are powerless and therefore inherently virtuous. Just as the Herodian spirit animates the Right to retain the throne through conspiracy and violence and corruption in the name of Jesus, it also blinds much of the Left to pursuit of power at the expense of anyone who does not fit their worldview. Consider the humiliating failure of college campus administrators to adequately speak out against calling for the expulsion and extermination of the Jews from Israel in the wake of the October 7th Hamas act of terror. The retention or pursuit of power often births in us paranoia and violence against our perceived enemies on “the other side”.

Religious elitism leads to a dullness and contempt for the gifts the Tradition holds that point us towards Jesus. In his fit of paranoia, Herod calls to himself the chief priests and teachers of the law, religious aristocrats who were willing to prop up his false reign because of the privilege it afforded them. The political, religious, and economic realities of the Roman Imperial system, administered through Herodian control, worked quite nicely for these men of high standing. They were the benefactors of an authoritarian regime whose main interest was in preserving the status quo. It is no surprise that while they had keen insight into the treasure trove of knowledge their expertise afforded them, they did not leave the place of privilege to seek the Christ Child for themselves. Dallas Willard taught us that, “familiarity leads to unfamiliarity, and unfamiliarity leads to contempt”. The chief priests’ lethargy betrays the fact that they were not the truly faithful shepherds many considered them to be, but more like the cowardly hired hands God prophesied against in passages like Ezekiel 34. As we keep a careful eye on the religious elite of first century Judea, we see their indifference to the birth of the messiah becomes fear, accusation and rejection at the end of Jesus’ life, save those few like Nicodemus who came to him for new life.

Are we not so often like these teachers of the law? Many of us were raised in the Christian household, taught the tenants of the faith through the scriptures since our earliest days, yet we find ourselves dulled and inoculated to the radical vitality of the Christmas story. Our own supposed familiarity, that we have “heard it all”, has bred a spiritual inertness. It is only a matter of time before lethargy gives way to contempt for the Christian faith, because we did not take seriously the invitation to seek Jesus. We have become spiritually lazy because our privilege allows it, and when the challenge comes we would rather preserve our way of living than risk anything to discover the living Christ.

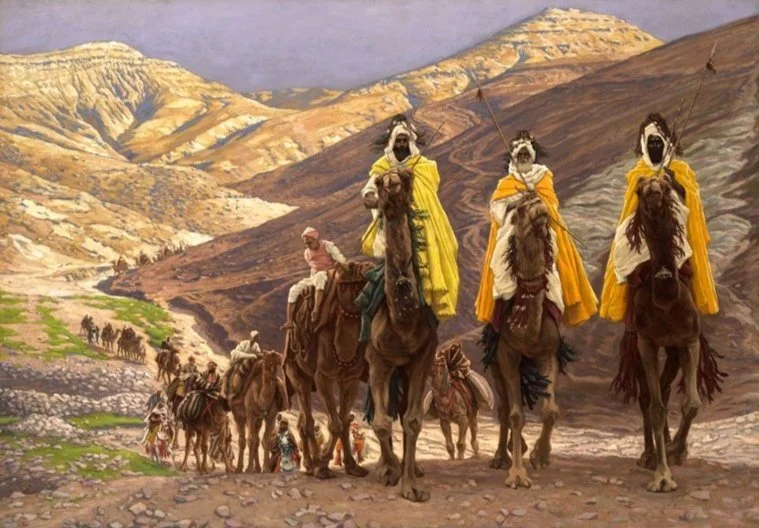

The Magi model for us, even as heretics and outsiders, the humility the Epiphany season invites to draw close to Jesus. Who were the Magi? They were not kings as many of our carols would attest to, but rather astrologers from the Eastern empire of Persia. Astrology was considered a legitimate science in the ancient world, although Judaism stood apart by condemning it as divination (Deut. 18:11 for example). Perhaps most fascinating of all, many scholars consider these Magi the descendants of the astrologers Daniel engaged with in the Babylonian exile. It stands to reason they may have been taught to read the Jewish scriptures to discern the advent of the Jewish messiah. Their gifts act as prophetic recognition of who this child was to become - gold for royalty, frankincense as a symbol for deity, and myrrh used for embalming dead bodies.

Matthew tells us these Magi approached the manger with a sense of joy that produced in them humble worship. In sharp contrast to the fearful paranoia of Herod or the cold indifference of the priests, the wise men are not concerned with retaining power or preserving privilege, but simply contemplating the Infant God. Although the scriptures do not tell us, I wonder how they were changed by this sacred encounter. What did they go home to? How did they see their profession, their authority, their own religion? We can only speculate, but I know that true, humble worship cannot help but transform us.

The Infant God beckons all - insiders and outsiders, poor and rich, Chosen and Rejected - to gaze in awe at the salvation of the world. This is the radical message of the Christmas story as it pierces our human assumptions about who is in and who is out. Mary and Joseph, the shepherds in the field and the heretics from the East, even Simeon and Anna at the temple in the following passage, show us that all are welcome to the stable, regardless of status, if we approach with wonder and humility. The Christmas story is indeed political, but in such a way as it challenges all our earthly politics. And we can imagine Matthew then turns the tables on us and asks, “why are you here?” Are we possessed by a Herodian spirit, in which religion is used to prop up a power plagued by suspicion and violence? Have we succumbed to the drone of religiosity like the teachers of the law, so lulled into spiritual sleep we cannot bother to get up and find the Christ? Or can we see in ourselves the heart of the Magi, that whether we have a lot or a little, whether or not we are considered insiders or outsiders, our hearts are drawn to the manger that becomes the throne of the True God amongst us?

O God, by the leading of a star you manifested your only Son to the Peoples of the earth: Lead us, who know you now by faith, to your presence, where we may see your glory face to face; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.